Updated:

Originally Published:

By the 1990s, Beta wasn’t just getting work—we were starting to shape it.

What began as a scrappy, after-hours outfit in the ’70s had become a focused, full-time operation by the ’80s. But the ’90s brought something new: trust. Utilities were coming to Beta not just to build—but to design, coordinate, and execute projects from the ground up.

The path to becoming a true EPC was still unfolding, but the foundation was forming. Beta’s engineering capabilities were growing, field leadership was solidifying, and the team was starting to take on more responsibility with less oversight. Bigger jobs, longer timelines, and deeper relationships followed.

In earlier years, Beta was often brought in late—after design decisions were made, or only once materials were ready to be installed. That started to shift in the ’90s. Clients began asking for input earlier. They wanted Beta’s field insight on constructability, schedules, and sourcing. They trusted our ability to keep projects moving.

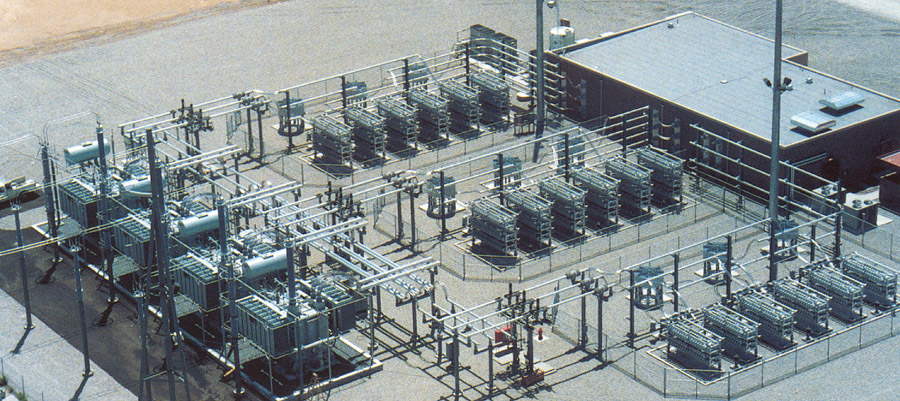

One example of that trust was the East Windsor Substation project in New Jersey. Completed in 1990 for Jersey Central Power & Light Company, this substation-only scope reflected Beta’s growing technical capabilities and ability to deliver on utility standards far from home base. It wasn’t just about building—it was about earning confidence in new markets.

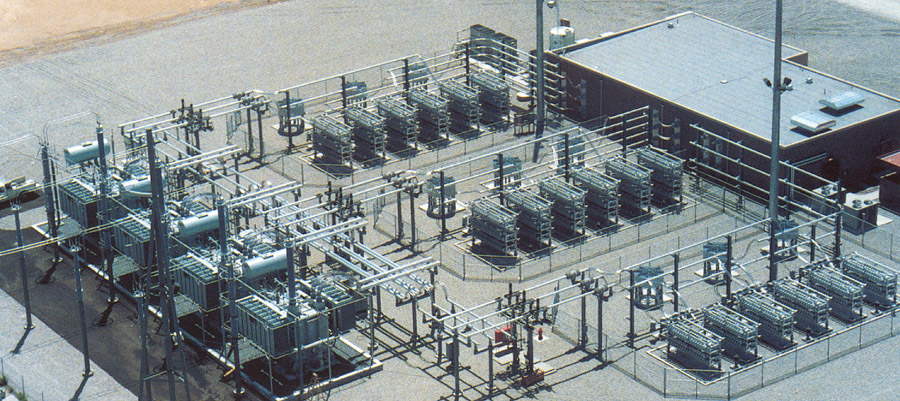

Beta was also beginning to show up in the high-tech space. In 1996, we delivered the Mead-Adelanto SVC project—a groundbreaking effort that included the EPC of two 387.5 MVAR static var compensators. Built in partnership with Siemens for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, this job demonstrated Beta’s growing sophistication in FACTS technology and large-scale, high-voltage delivery. It also showed our ability to partner with major players and deliver in some of the most demanding power environments in the country.

These weren’t just projects—they were signals that Beta could do more.

"All of our growth was organic," said Marvin Veuleman, who served as Beta’s President from 1991 to 2016. "That made it tough, but also rewarding. We had to hire, train, and develop people from the ground up. But that meant they were loyal. They knew our values. They were fully engaged."

Beta’s early culture—built on ownership and accountability—continued to drive the company forward. But in the ’90s, that mindset was backed by something else: experience.

Field leads who had once been part of Beta’s first crews were now mentoring new team members. Engineers who had come from other Crest companies began shaping Beta’s technical capabilities. Proposal writers, schedulers, and planners were brought in to support growing complexity. Project management, once an informal extension of other roles, began to stand on its own. As scopes grew and schedules tightened, Beta recognized the need for dedicated leaders to coordinate every aspect of a job from kickoff to close out. Project managers became the glue—linking clients, engineers, crews, and vendors—and their role quickly became indispensable.

The company was still lean, but no longer learning everything on the fly. And though there wasn’t a formal growth plan, there was clear direction: do good work, build good teams, and the rest would follow.

Beta didn’t market itself much. There were no ad campaigns or sales pitches. Just projects—done right, or not at all. That approach worked. More utilities came calling. More teammates chose to stay. And Beta started becoming the kind of company people looked for when they needed a job handled with care.

By the end of the 1990s, Beta had a growing list of clients, a deepening bench of talent, and a quiet but durable reputation: not just capable, but dependable. Not just committed, but consistent. Beta wasn’t just executing work—we were earning the kind of trust that defines an EPC partner. With each project, our role expanded, our teams matured, and our track record deepened. We weren’t just aiming for that reputation anymore—we were living it.

Updated:

July 30, 2025

Updated:

Originally Published:

By the 1990s, Beta wasn’t just getting work—we were starting to shape it.

What began as a scrappy, after-hours outfit in the ’70s had become a focused, full-time operation by the ’80s. But the ’90s brought something new: trust. Utilities were coming to Beta not just to build—but to design, coordinate, and execute projects from the ground up.

The path to becoming a true EPC was still unfolding, but the foundation was forming. Beta’s engineering capabilities were growing, field leadership was solidifying, and the team was starting to take on more responsibility with less oversight. Bigger jobs, longer timelines, and deeper relationships followed.

In earlier years, Beta was often brought in late—after design decisions were made, or only once materials were ready to be installed. That started to shift in the ’90s. Clients began asking for input earlier. They wanted Beta’s field insight on constructability, schedules, and sourcing. They trusted our ability to keep projects moving.

One example of that trust was the East Windsor Substation project in New Jersey. Completed in 1990 for Jersey Central Power & Light Company, this substation-only scope reflected Beta’s growing technical capabilities and ability to deliver on utility standards far from home base. It wasn’t just about building—it was about earning confidence in new markets.

Beta was also beginning to show up in the high-tech space. In 1996, we delivered the Mead-Adelanto SVC project—a groundbreaking effort that included the EPC of two 387.5 MVAR static var compensators. Built in partnership with Siemens for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, this job demonstrated Beta’s growing sophistication in FACTS technology and large-scale, high-voltage delivery. It also showed our ability to partner with major players and deliver in some of the most demanding power environments in the country.

These weren’t just projects—they were signals that Beta could do more.

"All of our growth was organic," said Marvin Veuleman, who served as Beta’s President from 1991 to 2016. "That made it tough, but also rewarding. We had to hire, train, and develop people from the ground up. But that meant they were loyal. They knew our values. They were fully engaged."

Beta’s early culture—built on ownership and accountability—continued to drive the company forward. But in the ’90s, that mindset was backed by something else: experience.

Field leads who had once been part of Beta’s first crews were now mentoring new team members. Engineers who had come from other Crest companies began shaping Beta’s technical capabilities. Proposal writers, schedulers, and planners were brought in to support growing complexity. Project management, once an informal extension of other roles, began to stand on its own. As scopes grew and schedules tightened, Beta recognized the need for dedicated leaders to coordinate every aspect of a job from kickoff to close out. Project managers became the glue—linking clients, engineers, crews, and vendors—and their role quickly became indispensable.

The company was still lean, but no longer learning everything on the fly. And though there wasn’t a formal growth plan, there was clear direction: do good work, build good teams, and the rest would follow.

Beta didn’t market itself much. There were no ad campaigns or sales pitches. Just projects—done right, or not at all. That approach worked. More utilities came calling. More teammates chose to stay. And Beta started becoming the kind of company people looked for when they needed a job handled with care.

By the end of the 1990s, Beta had a growing list of clients, a deepening bench of talent, and a quiet but durable reputation: not just capable, but dependable. Not just committed, but consistent. Beta wasn’t just executing work—we were earning the kind of trust that defines an EPC partner. With each project, our role expanded, our teams matured, and our track record deepened. We weren’t just aiming for that reputation anymore—we were living it.

Related Services: